The entirely theoretical cloud of icy space debris marks the frontiers of our solar system.

By Joshua Rapp Learn | Published: Thursday, August 5, 2021

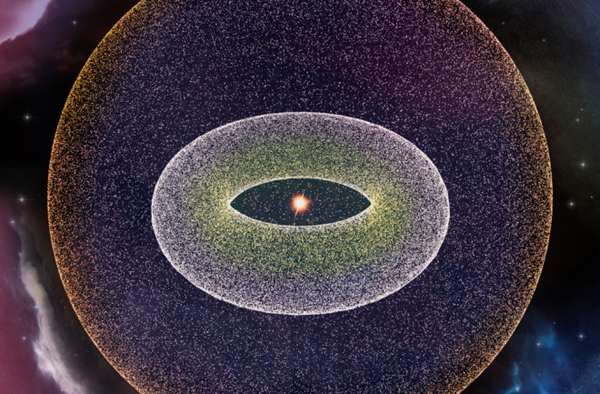

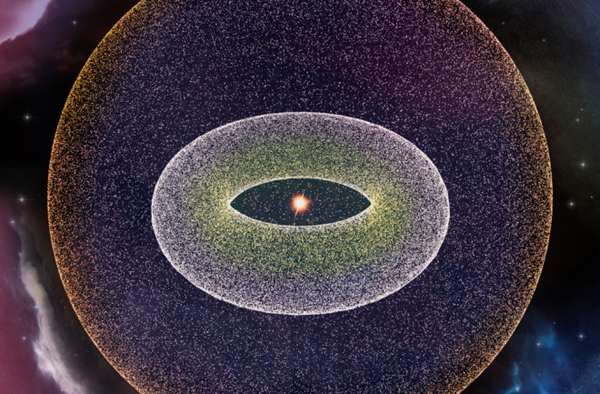

The Oort cloud represents the very edges of our solar system. The thinly dispersed collection of icy material starts roughly 200 times farther away from the sun than Pluto and stretches halfway to our sun’s nearest starry neighbor, Alpha Centauri. We know so little about it that its very existence is theoretical — the material that makes up this cloud has never been glimpsed by even our most powerful telescopes, except when some of it breaks free.

“For the foreseeable future, the bodies in the Oort cloud are too far away to be directly imaged,” says a spokesperson from NASA. “They are small, faint, and moving slowly.”

Aside from theoretical models, most of what we know about this mysterious area is told from the visitors that sometimes swing our way every 200 years or more — long period comets. “[The comets] have very important information about the origin of the solar system,” says Jorge Correa Otto, a planetary scientist the Argentina National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET).

The Oort cloud’s inner edge is believed to begin roughly 1,000 to 2,000 astronomical units from our sun. Since an astronomical unit is measured as the distance between the Earth and the sun, this means it’s at least a thousand times farther from the sun than we are. The outer edge is thought to go as far as 100,000 astronomical units away, which is halfway to Alpha Centauri. “Most of our knowledge about the structure of the Oort cloud comes from theoretical modeling of the formation and evolution of the solar system,” the NASA spokesperson says.

While there are many theories about its formation and existence, many believe that the Oort cloud was created when many of the planets in our solar system were formed roughly 4.6 billion years ago. Similar to the way the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter sprung to life, the Oort cloud likely represents material left over from the formation of giant planets like Jupiter, Neptune, Uranus and Saturn. The movements of these planets as they came to occupy their current positions pushed that material past Neptune’s orbit, Correa Otto says.

Another recent study holds that some of the material in the Oort cloud may be gathered as our sun steals comets orbiting other stars. Basically, the theory is that comets with extremely long distances around our neighboring stars get diverted when coming into closer range to our sun, at which point they stick around in the Oort cloud.

The composition of the icy objects that form the Oort cloud is thought to be similar to that of the Kuiper Belt, a flat, disk-shaped area beyond the orbit of Neptune we know more about. The Kuiper Belt also consists of icy objects leftover from planet formation in the early history of our solar system. Pluto is probably the most famous object in this area, though NASA’s New Horizons space probe flew by another double-lobed object in 2019 called Arrokoth — currently the most distant object in our solar system explored up close, according to NASA.

“Bodies in the Oort cloud, Kuiper belt, and the inner solar system are all believed to have formed together, and gravitational dynamics in the solar system kicked some of them out,” the NASA spokesperson says.

Estonian philosopher Ernst Öpik first theorized that long-period comets might come from an area at the edge of our solar system. Then, Dutch astronomer Jan Oort predicted the existence of his cloud in the 1950s to better understand the paradox of long-period comets.

Oort's theory was that comets would eventually strike the sun or a planet, or get ejected from the solar system when coming into closer contact with the strong orbit of one of those large bodies. Furthermore, the tails that we see on comets are made of gasses burned off from the sun’s radiation. If they made too many passes close to the sun, this material would have burned off. So they must not have spent all their existence in their current orbits. “Occasionally, Oort cloud bodies will get kicked out of their orbits, probably due to gravitational interactions with other Oort cloud bodies, and come visit the inner solar system as comets,” the NASA spokesperson says.

Correa Otto says that the direction of comets also supports the Oort cloud’s spherical shape. If it was shaped more like a disk, similar to the Kuiper Belt, comets would follow a more predictable direction. But the comets that pass by us come from random directions. As such, it seems the Oort cloud is more of a shell or bubble around our solar system than a disk like the Kuiper Belt. These long-period comets include C/2013 A1 Siding Spring, which passed close to Mars in 2014 and won’t be seen again for another 740,000 years.

“No object has been observed in the distant Oort cloud itself, leaving it a theoretical concept for the time being. But it remains the most widely-accepted explanation for the origin of long-period comets,” NASA says.

The Oort cloud, if it indeed exists, likely isn’t unique to our own solar system. Correa Otto says that some astronomers believe these clouds exist around many solar systems. The trouble is, we can’t even yet see our own, let alone those of our neighboring systems. The Voyager 1 spacecraft is headed in that direction — it’s projected to reach the inner edge of our Oort cloud in roughly 300 years. Unfortunately, Voyager will have long since stopped working.

“Even if it did [still work], the Sun’s light is so faint, and the distances so vast, that it would be unlikely to fly close enough to something to image it,” the NASA spokesperson says. In other words, it would be difficult to tell you’re in the Oort cloud even if you were right inside it.